高度な演算子

日本語を消す 英語を消す下記URLから引用し、日本語訳をつけてみました

https://docs.swift.org/swift-book/documentation/the-swift-programming-language/advancedoperators

Define custom operators, perform bitwise operations, and use builder syntax.

カスタム演算子を定義し、ビットごとの演算を実行し、ビルダー構文を使用します。

In addition to the operators described in Basic Operators, Swift provides several advanced operators that perform more complex value manipulation. These include all of the bitwise and bit shifting operators you will be familiar with from C and Objective-C.

「基本的な演算子」で説明されている演算子に加えて、Swift には、より複雑な値の操作を実行するいくつかの高度な演算子が用意されています。 これらには、C や Objective-C でよく知られているビットごとの演算子とビット シフト演算子がすべて含まれます。

Unlike arithmetic operators in C, arithmetic operators in Swift don’t overflow by default. Overflow behavior is trapped and reported as an error. To opt in to overflow behavior, use Swift’s second set of arithmetic operators that overflow by default, such as the overflow addition operator (&+). All of these overflow operators begin with an ampersand (&).

C の算術演算子とは異なり、Swift の算術演算子はデフォルトではオーバーフローしません。 オーバーフロー動作はトラップされ、エラーとして報告されます。 オーバーフロー動作をオプトインするには、オーバーフロー加算演算子 (&+) など、デフォルトでオーバーフローする Swift の算術演算子の 2 番目のセットを使用します。 これらのオーバーフロー演算子はすべてアンパサンド (&) で始まります。

When you define your own structures, classes, and enumerations, it can be useful to provide your own implementations of the standard Swift operators for these custom types. Swift makes it easy to provide tailored implementations of these operators and to determine exactly what their behavior should be for each type you create.

独自の構造体、クラス、列挙型を定義する場合、これらのカスタム型に対して標準の Swift 演算子の独自の実装を提供すると便利です。 Swift を使用すると、これらの演算子のカスタマイズされた実装を提供し、作成する型ごとに演算子の動作がどうあるべきかを正確に決定することが簡単になります。

You’re not limited to the predefined operators. Swift gives you the freedom to define your own custom infix, prefix, postfix, and assignment operators, with custom precedence and associativity values. These operators can be used and adopted in your code like any of the predefined operators, and you can even extend existing types to support the custom operators you define.

事前定義された演算子に制限されません。 Swift では、カスタムの優先順位と結合性の値を使用して、独自のカスタム中置演算子、接頭辞、後置演算子、代入演算子を自由に定義できます。 これらの演算子は、定義済みの演算子と同様にコード内で使用および採用でき、定義したカスタム演算子をサポートするように既存の型を拡張することもできます。

Bitwise Operators

ビット演算子

Bitwise operators enable you to manipulate the individual raw data bits within a data structure. They’re often used in low-level programming, such as graphics programming and device driver creation. Bitwise operators can also be useful when you work with raw data from external sources, such as encoding and decoding data for communication over a custom protocol.

ビットごとの演算子を使用すると、データ構造内の個々の生データ ビットを操作できます。 これらは、グラフィックス プログラミングやデバイス ドライバーの作成などの低レベル プログラミングでよく使用されます。 ビット単位の演算子は、カスタム プロトコルを介した通信のためのデータのエンコードやデコードなど、外部ソースからの生データを操作する場合にも役立ちます。

Swift supports all of the bitwise operators found in C, as described below.

Swift は、以下で説明するように、C にあるすべてのビット演算子をサポートしています。

Bitwise NOT Operator

ビット単位の NOT 演算子

The bitwise NOT operator (~) inverts all bits in a number:

ビット単位の NOT 演算子 (~) は、数値内のすべてのビットを反転します。

The bitwise NOT operator is a prefix operator, and appears immediately before the value it operates on, without any white space:

ビット単位の NOT 演算子は接頭辞演算子であり、演算対象となる値の直前に空白なしで現れます。

let initialBits: UInt8 = 0b00001111

let invertedBits = ~initialBits // equals 11110000

UInt8 integers have eight bits and can store any value between 0 and 255. This example initializes a UInt8 integer with the binary value 00001111, which has its first four bits set to 0, and its second four bits set to 1. This is equivalent to a decimal value of 15.

UInt8 整数には 8 ビットがあり、0 から 255 までの任意の値を格納できます。この例では、UInt8 整数をバイナリ値 00001111 で初期化し、最初の 4 ビットが 0 に設定され、次の 4 ビットが 1 に設定されます。これは次と同等です。 10 進数値の 15。

The bitwise NOT operator is then used to create a new constant called invertedBits, which is equal to initialBits, but with all of the bits inverted. Zeros become ones, and ones become zeros. The value of invertedBits is 11110000, which is equal to an unsigned decimal value of 240.

次に、ビット単位の NOT 演算子を使用して、invertedBits という新しい定数が作成されます。これは、initialBits と同じですが、すべてのビットが反転されています。 ゼロは 1 になり、1 はゼロになります。 invertedBits の値は 11110000 で、符号なし 10 進数値の 240 に相当します。

Bitwise AND Operator

ビット単位の AND 演算子

The bitwise AND operator (&) combines the bits of two numbers. It returns a new number whose bits are set to 1 only if the bits were equal to 1 in both input numbers:

ビット単位の AND 演算子 (&) は、2 つの数値のビットを結合します。 両方の入力数値のビットが 1 に等しい場合にのみ、ビットが 1 に設定された新しい数値を返します。

In the example below, the values of firstSixBits and lastSixBits both have four middle bits equal to 1. The bitwise AND operator combines them to make the number 00111100, which is equal to an unsigned decimal value of 60:

以下の例では、firstSixBits と lastSixBits の値はどちらも 1 に等しい 4 つの中間ビットを持っています。ビットごとの AND 演算子でそれらを結合して数値 00111100 を作り、これは符号なし 10 進数値の 60 に相当します。

let firstSixBits: UInt8 = 0b11111100

let lastSixBits: UInt8 = 0b00111111

let middleFourBits = firstSixBits & lastSixBits // equals 00111100

Bitwise OR Operator

ビット単位の OR 演算子

The bitwise OR operator (|) compares the bits of two numbers. The operator returns a new number whose bits are set to 1 if the bits are equal to 1 in either input number:

ビット単位の OR 演算子 (|) は、2 つの数値のビットを比較します。 いずれかの入力数値のビットが 1 に等しい場合、演算子はビットが 1 に設定された新しい数値を返します。

In the example below, the values of someBits and moreBits have different bits set to 1. The bitwise OR operator combines them to make the number 11111110, which equals an unsigned decimal of 254:

以下の例では、someBits と moreBits の値には、異なるビットが 1 に設定されています。ビットごとの OR 演算子でそれらを結合し、数値 11111110 を作成します。これは、符号なし 10 進数の 254 に相当します。

let someBits: UInt8 = 0b10110010

let moreBits: UInt8 = 0b01011110

let combinedbits = someBits | moreBits // equals 11111110

Bitwise XOR Operator

ビット単位の XOR 演算子

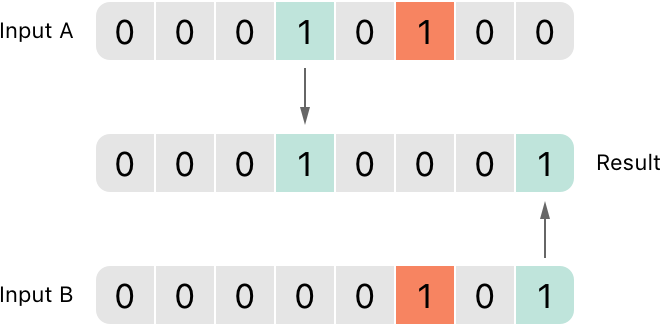

The bitwise XOR operator, or “exclusive OR operator” (^), compares the bits of two numbers. The operator returns a new number whose bits are set to 1 where the input bits are different and are set to 0 where the input bits are the same:

ビットごとの XOR 演算子、つまり「排他的 OR 演算子」(^) は、2 つの数値のビットを比較します。 演算子は、入力ビットが異なる場合にはビットが 1 に設定され、入力ビットが同じ場合には 0 に設定される新しい数値を返します。

In the example below, the values of firstBits and otherBits each have a bit set to 1 in a location that the other does not. The bitwise XOR operator sets both of these bits to 1 in its output value. All of the other bits in firstBits and otherBits match and are set to 0 in the output value:

以下の例では、firstBits と otherBits の値のそれぞれのビットが、他方はそうでない所で 1 に設定されています。 ビットごとの XOR 演算子は、出力値のこれらのビットの両方を 1 に設定しています。 firstBits と otherBits の他のビットはすべて一致し、出力値では 0 に設定されます。

let firstBits: UInt8 = 0b00010100

let otherBits: UInt8 = 0b00000101

let outputBits = firstBits ^ otherBits // equals 00010001

Bitwise Left and Right Shift Operators

ビット単位の左シフト演算子と右シフト演算子

The bitwise left shift operator (<<) and bitwise right shift operator (>>) move all bits in a number to the left or the right by a certain number of places, according to the rules defined below.

ビット単位の左シフト演算子(<<)とビット単位の右シフト演算子(>>)は、以下に定義されているルールに従って、数値内のすべてのビットを特定の桁数だけ左または右に移動します。

Bitwise left and right shifts have the effect of multiplying or dividing an integer by a factor of two. Shifting an integer’s bits to the left by one position doubles its value, whereas shifting it to the right by one position halves its value.

ビット単位の左右シフトには、整数を 2 の係数で乗算または除算する効果があります。 整数のビットを左に 1 位置シフトすると値が 2 倍になり、右に 1 位置シフトすると値が半分になります。

Shifting Behavior for Unsigned Integers

符号なし整数のシフト動作

The bit-shifting behavior for unsigned integers is as follows:

符号なし整数のビットシフト動作は次のとおりです。

- Existing bits are moved to the left or right by the requested number of places.

- 既存のビットは、要求された桁数だけ左または右に移動されます。

- Any bits that are moved beyond the bounds of the integer’s storage are discarded.

- 整数のストレージの境界を超えて移動されたビットはすべて破棄されます。

- Zeros are inserted in the spaces left behind after the original bits are moved to the left or right.

- 元のビットが左または右に移動された後に残ったスペースにゼロが挿入されます。

This approach is known as a logical shift.

このアプローチは論理シフトとして知られています。

The illustration below shows the results of 11111111 << 1 (which is 11111111 shifted to the left by 1 place), and 11111111 >> 1 (which is 11111111 shifted to the right by 1 place). Green numbers are shifted, gray numbers are discarded, and pink zeros are inserted:

下の図は、11111111 << 1(11111111を左に1桁ずらしたもの)と11111111 >> 1(11111111を右に1桁ずらしたもの)の結果を示しています。 緑色の数値はシフトされ、灰色の数値は破棄され、ピンク色のゼロが挿入されます。

Here’s how bit shifting looks in Swift code:

Swift コードでのビットシフトは次のようになります。

let shiftBits: UInt8 = 4 // 00000100 in binary

shiftBits << 1 // 00001000

shiftBits << 2 // 00010000

shiftBits << 5 // 10000000

shiftBits << 6 // 00000000

shiftBits >> 2 // 00000001

You can use bit shifting to encode and decode values within other data types:

ビット シフトを使用して、他のデータ型内の値をエンコードおよびデコードできます。

let pink: UInt32 = 0xCC6699

let redComponent = (pink & 0xFF0000) >> 16 // redComponent is 0xCC, or 204

let greenComponent = (pink & 0x00FF00) >> 8 // greenComponent is 0x66, or 102

let blueComponent = pink & 0x0000FF // blueComponent is 0x99, or 153

くまの解説

0からFまで使う16進数は、0と1を使う2進数の4ビット分(16 = 2 * 2 * 2 * 2 = 2^4)を表現できます。シフトは2進数のビット単位で移動させるので、16進数を1桁シフトする場合は、2進数の4ビット分、つまり 4 シフトさせます。つまり >> 16 は 右へ4桁シフトさせることになります。

This example uses a UInt32 constant called pink to store a Cascading Style Sheets color value for the color pink. The CSS color value #CC6699 is written as 0xCC6699 in Swift’s hexadecimal number representation. This color is then decomposed into its red (CC), green (66), and blue (99) components by the bitwise AND operator (&) and the bitwise right shift operator (>>).

この例では、pink という UInt32 定数を使用して、ピンク色のカスケード スタイル シートのカラー値を保存します。 CSS カラー値 #CC6699 は、Swift の 16 進数表現では 0xCC6699 として記述されます。 次に、この色は、ビット単位の AND 演算子 (&) とビット単位の右シフト演算子 (>>) によって、赤 (CC)、緑 (66)、および青 (99) のコンポーネントに分解されます。

The red component is obtained by performing a bitwise AND between the numbers 0xCC6699 and 0xFF0000. The zeros in 0xFF0000 effectively “mask” the second and third bytes of 0xCC6699, causing the 6699 to be ignored and leaving 0xCC0000 as the result.

赤色のコンポーネントは、数値 0xCC6699 と 0xFF0000 の間でビット単位の AND を実行することで取得されます。 0xFF0000 のゼロは、0xCC6699 の 2 番目と 3 番目のバイトを事実上「マスク」し、6699 が無視され、結果として 0xCC0000 が残ります。

This number is then shifted 16 places to the right (>> 16). Each pair of characters in a hexadecimal number uses 8 bits, so a move 16 places to the right will convert 0xCC0000 into 0x0000CC. This is the same as 0xCC, which has a decimal value of 204.

この数値は右に 16 桁シフトされます (>> 16)。 16 進数の文字の各ペアは 8 ビットを使用するため、右に 16 桁移動すると、0xCC0000 が 0x0000CC に変換されます。 これは、10 進数値 204 を持つ 0xCC と同じです。

Similarly, the green component is obtained by performing a bitwise AND between the numbers 0xCC6699 and 0x00FF00, which gives an output value of 0x006600. This output value is then shifted eight places to the right, giving a value of 0x66, which has a decimal value of 102.

同様に、緑色のコンポーネントは、数値 0xCC6699 と 0x00FF00 の間でビット単位の AND を実行することで取得され、出力値 0x006600 が得られます。 この出力値は右に 8 桁シフトされ、10 進数値が 102 になる値 0x66 が得られます。

Finally, the blue component is obtained by performing a bitwise AND between the numbers 0xCC6699 and 0x0000FF, which gives an output value of 0x000099. Because 0x000099 already equals 0x99, which has a decimal value of 153, this value is used without shifting it to the right,

最後に、数値 0xCC6699 と 0x0000FF の間でビット単位の AND を実行することで青色のコンポーネントが取得され、出力値 0x000099 が得られます。 0x000099 はすでに 0x99 (10 進数値 153) と等しいため、この値は右にシフトせずに使用されます。

Shifting Behavior for Signed Integers

符号付き整数のシフト動作

The shifting behavior is more complex for signed integers than for unsigned integers, because of the way signed integers are represented in binary. (The examples below are based on 8-bit signed integers for simplicity, but the same principles apply for signed integers of any size.)

符号付き整数はバイナリで表現される方法により、シフト動作は符号なし整数よりも符号付き整数の方が複雑になります。 (以下の例は、簡単にするために 8 ビットの符号付き整数に基づいていますが、同じ原則が任意のサイズの符号付き整数に適用されます。)

Signed integers use their first bit (known as the sign bit) to indicate whether the integer is positive or negative. A sign bit of 0 means positive, and a sign bit of 1 means negative.

符号付き整数は、最初のビット(符号ビットと呼ばれる)を使用して、整数が正か負かを示します。 符号ビット 0 は正を意味し、符号ビット 1 は負を意味します。

The remaining bits (known as the value bits) store the actual value. Positive numbers are stored in exactly the same way as for unsigned integers, counting upwards from 0. Here’s how the bits inside an Int8 look for the number 4:

残りのビット(値ビットと呼ばれる)には実際の値が保存されます。 正の数値は、符号なし整数の場合とまったく同じ方法で保存され、0 からカウントアップされます。Int8 内のビットが数値 4 をどのように探すかは次のとおりです。

The sign bit is 0 (meaning “positive”), and the seven value bits are just the number 4, written in binary notation.

符号ビットは 0 (「正」を意味します) で、7 つの値ビットは 2 進数表記で書かれた単なる数値 4 です。

Negative numbers, however, are stored differently. They’re stored by subtracting their absolute value from 2 to the power of n, where n is the number of value bits. An eight-bit number has seven value bits, so this means 2 to the power of 7, or 128.

ただし、負の数値は異なる方法で格納されます。 これらは、絶対値を 2 の n 乗から減算することによって保存されます。ここで、n は値のビット数です。 8 ビットの数値には 7 つの値ビットがあるため、これは 2 の 7 乗、つまり 128 を意味します。

Here’s how the bits inside an Int8 look for the number -4:

Int8 内のビットが数値 -4 をどのように探すかは次のとおりです。

This time, the sign bit is 1 (meaning “negative”), and the seven value bits have a binary value of 124 (which is 128 - 4):

今回は、符号ビットは 1 (「負」を意味します) で、7 つの値ビットのバイナリ値は 124 (128 - 4) です。

This encoding for negative numbers is known as a two’s complement representation. It may seem an unusual way to represent negative numbers, but it has several advantages.

負の数のこのエンコードは、2 の補数表現として知られています。 負の数を表す珍しい方法のように思えるかもしれませんが、いくつかの利点があります。

First, you can add -1 to -4, simply by performing a standard binary addition of all eight bits (including the sign bit), and discarding anything that doesn’t fit in the eight bits once you’re done:

まず、-1 を -4 に加算することができます。これは、8 ビットすべて (符号ビットを含む) の標準的なバイナリ加算を実行し、完了後に 8 ビットに収まらないものを破棄するだけです。

Second, the two’s complement representation also lets you shift the bits of negative numbers to the left and right like positive numbers, and still end up doubling them for every shift you make to the left, or halving them for every shift you make to the right. To achieve this, an extra rule is used when signed integers are shifted to the right: When you shift signed integers to the right, apply the same rules as for unsigned integers, but fill any empty bits on the left with the sign bit, rather than with a zero.

第 2 に、2 の補数表現を使用すると、負の数のビットを正の数と同様に左右にシフトすることができ、それでも最終的に左にシフトするたびに 2 倍になり、右にシフトするたびに 2 分の 1 になります。 。 これを達成するために、符号付き整数を右にシフトするときに追加のルールが使用されます。符号付き整数を右にシフトするときは、符号なし整数の場合と同じルールを適用しますが、左側の空のビットは符号ビットで埋めます。ゼロではありません。

This action ensures that signed integers have the same sign after they’re shifted to the right, and is known as an arithmetic shift.

このアクションは、符号付き整数が右にシフトされた後に同じ符号を持つようにするもので、算術シフトとして知られています。

Because of the special way that positive and negative numbers are stored, shifting either of them to the right moves them closer to zero. Keeping the sign bit the same during this shift means that negative integers remain negative as their value moves closer to zero.

正の数値と負の数値は特殊な方法で格納されるため、どちらかを右にシフトするとゼロに近づきます。 このシフト中に符号ビットを同じに保つということは、負の整数の値がゼロに近づいても、負の整数は負のままであることを意味します。

Overflow Operators

オーバーフロー演算子

If you try to insert a number into an integer constant or variable that can’t hold that value, by default Swift reports an error rather than allowing an invalid value to be created. This behavior gives extra safety when you work with numbers that are too large or too small.

その値を保持できない整定数または変数に数値を挿入しようとすると、Swift はデフォルトで無効な値の作成を許可するのではなく、エラーを報告します。 この動作により、大きすぎる数値や小さすぎる数値を扱う際の安全性がさらに高まります。

For example, the Int16 integer type can hold any signed integer between -32768 and 32767. Trying to set an Int16 constant or variable to a number outside of this range causes an error:

たとえば、Int16 整数型は、-32768 から 32767 までの任意の符号付き整数を保持できます。Int16 定数または変数をこの範囲外の数値に設定しようとすると、エラーが発生します。

var potentialOverflow = Int16.max

// potentialOverflow equals 32767, which is the maximum value an Int16 can hold

potentialOverflow += 1

// this causes an error

Providing error handling when values get too large or too small gives you much more flexibility when coding for boundary value conditions.

値が大きすぎるか小さすぎる場合のエラー処理を提供すると、境界値条件をコーディングする際の柔軟性が大幅に高まります。

However, when you specifically want an overflow condition to truncate the number of available bits, you can opt in to this behavior rather than triggering an error. Swift provides three arithmetic overflow operators that opt in to the overflow behavior for integer calculations. These operators all begin with an ampersand (&):

ただし、オーバーフロー条件によって使用可能なビット数を切り捨てることが特に必要な場合は、エラーをトリガーするのではなく、この動作をオプトインできます。 Swift には、整数計算のオーバーフロー動作を選択する 3 つの算術オーバーフロー演算子が用意されています。 これらの演算子はすべてアンパサンド (&) で始まります。

- Overflow addition (

&+) - オーバーフロー加算 (

&+) - Overflow subtraction (

&-) - オーバーフロー減算 (

&-) - Overflow multiplication (

&*) - オーバーフロー乗算 (

&*)

Value Overflow

値のオーバーフロー

Numbers can overflow in both the positive and negative direction.

数値は正負の両方向にオーバーフローする可能性があります。

Here’s an example of what happens when an unsigned integer is allowed to overflow in the positive direction, using the overflow addition operator (&+):

以下は、オーバーフロー加算演算子 (&+) を使用して、符号なし整数が正の方向にオーバーフローできる場合に何が起こるかを示す例です。

var unsignedOverflow = UInt8.max

// unsignedOverflow equals 255, which is the maximum value a UInt8 can hold

unsignedOverflow = unsignedOverflow &+ 1

// unsignedOverflow is now equal to 0

The variable unsignedOverflow is initialized with the maximum value a UInt8 can hold (255, or 11111111 in binary). It’s then incremented by 1 using the overflow addition operator (&+). This pushes its binary representation just over the size that a UInt8 can hold, causing it to overflow beyond its bounds, as shown in the diagram below. The value that remains within the bounds of the UInt8 after the overflow addition is 00000000, or zero.

変数 unsignedOverflow は、UInt8 が保持できる最大値 (255、またはバイナリで 11111111) で初期化されます。 次に、オーバーフロー加算演算子(&+)を使用して 1 増加します。 これにより、UInt8 が保持できるサイズをわずかに超えるバイナリ表現が押し出され、以下の図に示すように、境界を超えてオーバーフローが発生します。 オーバーフロー追加後に UInt8 の範囲内に残る値は、00000000、つまりゼロです。

Something similar happens when an unsigned integer is allowed to overflow in the negative direction. Here’s an example using the overflow subtraction operator (&-):

符号なし整数が負の方向にオーバーフローできる場合にも、同様のことが起こります。 オーバーフロー減算演算子 (&-) を使用した例を次に示します。

var unsignedOverflow = UInt8.min

// unsignedOverflow equals 0, which is the minimum value a UInt8 can hold

unsignedOverflow = unsignedOverflow &- 1

// unsignedOverflow is now equal to 255

The minimum value that a UInt8 can hold is zero, or 00000000 in binary. If you subtract 1 from 00000000 using the overflow subtraction operator (&-), the number will overflow and wrap around to 11111111, or 255 in decimal.

UInt8 が保持できる最小値はゼロ、またはバイナリで 00000000 です。 オーバーフロー減算演算子(&-)を使用して 00000000 から 1 を引くと、数値はオーバーフローして 11111111、つまり 10 進数で 255 に戻ります。

Overflow also occurs for signed integers. All addition and subtraction for signed integers is performed in bitwise fashion, with the sign bit included as part of the numbers being added or subtracted, as described in Bitwise Left and Right Shift Operators.

オーバーフローは符号付き整数の場合にも発生します。 符号付き整数の加算と減算はすべてビット単位で実行され、ビット単位の左シフト演算子と右シフト演算子で説明されているように、加算または減算される数値の一部として符号ビットが含まれます。

var signedOverflow = Int8.min

// signedOverflow equals -128, which is the minimum value an Int8 can hold

signedOverflow = signedOverflow &- 1

// signedOverflow is now equal to 127

The minimum value that an Int8 can hold is -128, or 10000000 in binary. Subtracting 1 from this binary number with the overflow operator gives a binary value of 01111111, which toggles the sign bit and gives positive 127, the maximum positive value that an Int8 can hold.

Int8 が保持できる最小値は -128、つまりバイナリで 10000000 です。 オーバーフロー演算子を使用してこの 2 進数から 1 を減算すると、2 進値 01111111 が得られ、これにより符号ビットが切り替わり、Int8 が保持できる正の最大値である正の 127 が得られます。

For both signed and unsigned integers, overflow in the positive direction wraps around from the maximum valid integer value back to the minimum, and overflow in the negative direction wraps around from the minimum value to the maximum.

符号付き整数と符号なし整数の両方で、正の方向のオーバーフローは有効な整数値の最大値から最小値までラップアラウンドし、負の方向のオーバーフローは最小値から最大値までラップアラウンドします。

Precedence and Associativity

優先順位と結合性

Operator precedence gives some operators higher priority than others; these operators are applied first.

演算子の優先順位により、一部の演算子が他の演算子よりも高い優先度が与えられます。 これらの演算子が最初に適用されます。

Operator associativity defines how operators of the same precedence are grouped together — either grouped from the left, or grouped from the right. Think of it as meaning “they associate with the expression to their left,” or “they associate with the expression to their right.”

演算子の結合性は、同じ優先順位の演算子をグループ化する方法 (左からグループ化するか、右からグループ化するかのいずれか) を定義します。 これは、「左側の表現と関連付けられる」または「右側の表現と関連付けられる」という意味だと考えてください。

It’s important to consider each operator’s precedence and associativity when working out the order in which a compound expression will be calculated. For example, operator precedence explains why the following expression equals 17.

複合式が計算される順序を決定するときは、各演算子の優先順位と結合性を考慮することが重要です。 たとえば、次の式が 17 に等しい理由は、演算子の優先順位によって説明されます。

2 + 3 % 4 * 5

// this equals 17

If you read strictly from left to right, you might expect the expression to be calculated as follows:

厳密に左から右に読むと、式は次のように計算されることが予想されます。

2plus3equals52足す3は55remainder4equals15余り4は11times5equals51かける5は5

However, the actual answer is 17, not 5. Higher-precedence operators are evaluated before lower-precedence ones. In Swift, as in C, the remainder operator (%) and the multiplication operator (*) have a higher precedence than the addition operator (+). As a result, they’re both evaluated before the addition is considered.

ただし、実際の答えは 5 ではなく 17 です。優先順位の高い演算子は、優先順位の低い演算子よりも前に評価されます。 Swift では、C と同様に、剰余演算子 (%) と乗算演算子 (*) は加算演算子 (+) よりも優先されます。 その結果、追加が考慮される前に両方が評価されます。

However, remainder and multiplication have the same precedence as each other. To work out the exact evaluation order to use, you also need to consider their associativity. Remainder and multiplication both associate with the expression to their left. Think of this as adding implicit parentheses around these parts of the expression, starting from their left:

ただし、剰余と乗算は互いに同じ優先順位を持ちます。 使用する正確な評価順序を決定するには、それらの結合性も考慮する必要があります。 剰余と乗算はどちらも左側の式に関連付けられます。 これは、式のこれらの部分を左から順に囲む暗黙の括弧を追加することだと考えてください。

2 + ((3 % 4) * 5)

(3 % 4) is 3, so this is equivalent to:

(3 % 4) は 3 であるため、これは次と同等です。

2 + (3 * 5)

(3 * 5) is 15, so this is equivalent to:

(3 * 5) は 15 であるため、これは次と同等です。

2 + 15

This calculation yields the final answer of 17.

この計算により、最終的な答えは 17 になります。

For information about the operators provided by the Swift standard library, including a complete list of the operator precedence groups and associativity settings, see Operator Declarations(Link:developer.apple.com).

演算子の優先順位グループと結合性設定の完全なリストを含む、Swift 標準ライブラリによって提供される演算子の詳細については、「演算子の宣言(Link:developer.apple.com)(英語)」を参照してください。

Note

注釈

Swift’s operator precedences and associativity rules are simpler and more predictable than those found in C and Objective-C. However, this means that they aren’t exactly the same as in C-based languages. Be careful to ensure that operator interactions still behave in the way you intend when porting existing code to Swift.

Swift の演算子の優先順位と結合規則は、C や Objective-C のものよりも単純で予測可能です。 ただし、これは、C ベースの言語とまったく同じではないことを意味します。 既存のコードを Swift に移植するときは、オペレーターの対話が意図したとおりに動作することを確認するように注意してください。

Operator Methods

演算子メソッド

Classes and structures can provide their own implementations of existing operators. This is known as overloading the existing operators.

クラスと構造体は、既存の演算子の独自の実装を提供できます。 これは、既存の演算子のオーバーロードとして知られています。

The example below shows how to implement the arithmetic addition operator (+) for a custom structure. The arithmetic addition operator is a binary operator because it operates on two targets and it’s an infix operator because it appears between those two targets.

以下の例は、カスタム構造体に算術加算演算子 (+) を実装する方法を示しています。 算術加算演算子は 2 つのターゲットで動作するため二項演算子であり、それら 2 つのターゲットの間に現れるため中置演算子です。

The example defines a Vector2D structure for a two-dimensional position vector (x, y), followed by a definition of an operator method to add together instances of the Vector2D structure:

この例では、2 次元位置ベクトル (x, y) の Vector2D 構造を定義し、続いて Vector2D 構造のインスタンスを加算する演算子メソッドの定義を行っています。

struct Vector2D {

var x = 0.0, y = 0.0

}

extension Vector2D {

static func + (left: Vector2D, right: Vector2D) -> Vector2D {

return Vector2D(x: left.x + right.x, y: left.y + right.y)

}

}

The operator method is defined as a type method on Vector2D, with a method name that matches the operator to be overloaded (+). Because addition isn’t part of the essential behavior for a vector, the type method is defined in an extension of Vector2D rather than in the main structure declaration of Vector2D. Because the arithmetic addition operator is a binary operator, this operator method takes two input parameters of type Vector2D and returns a single output value, also of type Vector2D.

演算子メソッドは、Vector2D 上の type メソッドとして定義され、オーバーロードされる演算子 (+) と一致するメソッド名が付けられます。 加算はベクターの本質的な動作の一部ではないため、型メソッドは Vector2D のメイン構造宣言ではなく、Vector2D の拡張機能で定義されます。 算術加算演算子は二項演算子であるため、この演算子メソッドは Vector2D 型の 2 つの入力パラメータを受け取り、同じく Vector2D 型の 1 つの出力値を返します。

In this implementation, the input parameters are named left and right to represent the Vector2D instances that will be on the left side and right side of the + operator. The method returns a new Vector2D instance, whose x and y properties are initialized with the sum of the x and y properties from the two Vector2D instances that are added together.

この実装では、+ 演算子の左側と右側にある Vector2D インスタンスを表すために、入力パラメータには left と right という名前が付けられています。 このメソッドは新しい Vector2D インスタンスを返します。その x プロパティと y プロパティは、合計された 2 つの Vector2D インスタンスの x プロパティと y プロパティの合計で初期化されます。

The type method can be used as an infix operator between existing Vector2D instances:

type メソッドは、既存の Vector2D インスタンス間の中置演算子として使用できます。

let vector = Vector2D(x: 3.0, y: 1.0)

let anotherVector = Vector2D(x: 2.0, y: 4.0)

let combinedVector = vector + anotherVector

// combinedVector is a Vector2D instance with values of (5.0, 5.0)

This example adds together the vectors (3.0, 1.0) and (2.0, 4.0) to make the vector (5.0, 5.0), as illustrated below.

この例では、以下に示すように、ベクトル (3.0, 1.0) と (2.0, 4.0) を加算してベクトル (5.0, 5.0) を作成します。

Prefix and Postfix Operators

前置演算子と後置演算子

The example shown above demonstrates a custom implementation of a binary infix operator. Classes and structures can also provide implementations of the standard unary operators. Unary operators operate on a single target. They’re prefix if they precede their target (such as -a) and postfix operators if they follow their target (such as b!).

上に示した例は、バイナリ中置演算子のカスタム実装を示しています。 クラスと構造体は、標準の単項演算子の実装を提供することもできます。 単項演算子は単一のターゲットを操作します。 ターゲットの前にある場合は接頭辞(-a など)、ターゲットの後にある場合は後置演算子(b! など)です。

You implement a prefix or postfix unary operator by writing the prefix or postfix modifier before the func keyword when declaring the operator method:

prefixまたはpostfixの単項演算子を実装するには、演算子メソッドを宣言するときに func キーワードの前に前置または後置修飾子を記述します。

extension Vector2D {

static prefix func - (vector: Vector2D) -> Vector2D {

return Vector2D(x: -vector.x, y: -vector.y)

}

}

The example above implements the unary minus operator (-a) for Vector2D instances. The unary minus operator is a prefix operator, and so this method has to be qualified with the prefix modifier.

上の例では、Vector2D インスタンスに単項マイナス演算子 (-a) を実装しています。 単項マイナス演算子は前置演算子であるため、このメソッドはprefix修飾子で修飾する必要があります。

For simple numeric values, the unary minus operator converts positive numbers into their negative equivalent and vice versa. The corresponding implementation for Vector2D instances performs this operation on both the x and y properties:

単純な数値の場合、単項マイナス演算子は正の数値を負の数値に変換し、その逆も行います。 Vector2D インスタンスの対応する実装は、x プロパティと y プロパティの両方に対してこの操作を実行します。

let positive = Vector2D(x: 3.0, y: 4.0)

let negative = -positive

// negative is a Vector2D instance with values of (-3.0, -4.0)

let alsoPositive = -negative

// alsoPositive is a Vector2D instance with values of (3.0, 4.0)

Compound Assignment Operators

複合代入演算子

Compound assignment operators combine assignment (=) with another operation. For example, the addition assignment operator (+=) combines addition and assignment into a single operation. You mark a compound assignment operator’s left input parameter type as inout, because the parameter’s value will be modified directly from within the operator method.

複合代入演算子は、代入 (=) と別の演算を組み合わせます。 たとえば、加算代入演算子 (+=) は、加算と代入を 1 つの演算に結合します。 パラメータの値は演算子メソッド内から直接変更されるため、複合代入演算子の左側の入力パラメータ タイプを inout としてマークします。

The example below implements an addition assignment operator method for Vector2D instances:

以下の例では、Vector2D インスタンスの加算代入演算子メソッドを実装しています。

extension Vector2D {

static func += (left: inout Vector2D, right: Vector2D) {

left = left + right

}

}

Because an addition operator was defined earlier, you don’t need to reimplement the addition process here. Instead, the addition assignment operator method takes advantage of the existing addition operator method, and uses it to set the left value to be the left value plus the right value:

加算演算子は前に定義されているため、ここで加算プロセスを再実装する必要はありません。 代わりに、加算代入演算子メソッドは既存の加算演算子メソッドを利用し、それを使用して左の値を左の値に右の値を加えた値に設定します。

var original = Vector2D(x: 1.0, y: 2.0)

let vectorToAdd = Vector2D(x: 3.0, y: 4.0)

original += vectorToAdd

// original now has values of (4.0, 6.0)

Note

注釈

It isn’t possible to overload the default assignment operator (=). Only the compound assignment operators can be overloaded. Similarly, the ternary conditional operator (a ? b : c) can’t be overloaded.

デフォルトの代入演算子 (=) をオーバーロードすることはできません。 複合代入演算子のみをオーバーロードできます。 同様に、三項条件演算子 (a ? b : c) はオーバーロードできません。

Equivalence Operators

等価演算子

By default, custom classes and structures don’t have an implementation of the equivalence operators, known as the equal to operator (==) and not equal to operator (!=). You usually implement the == operator, and use the Swift standard library’s default implementation of the != operator that negates the result of the == operator. There are two ways to implement the == operator: You can implement it yourself, or for many types, you can ask Swift to synthesize an implementation for you. In both cases, you add conformance to the Swift standard library’s Equatable protocol.

デフォルトでは、カスタム クラスと構造には、等価演算子 (==) および不等価演算子 (!=) と呼ばれる等価演算子の実装がありません。 通常、== 演算子を実装し、== 演算子の結果を否定する Swift 標準ライブラリの != 演算子のデフォルト実装を使用します。 == 演算子を実装するには 2 つの方法があります。自分で実装することも、多くのタイプでは、Swift に実装を合成するよう依頼することもできます。 どちらの場合も、Swift 標準ライブラリの Equatable プロトコルへの準拠を追加します。

You provide an implementatioan of the == operator in the same way as you implement other infix operators:

== 演算子の実装は、他の中置演算子を実装するのと同じ方法で提供します。

extension Vector2D: Equatable {

static func == (left: Vector2D, right: Vector2D) -> Bool {

return (left.x == right.x) && (left.y == right.y)

}

}

The example above implements an == operator to check whether two Vector2D instances have equivalent values. In the context of Vector2D, it makes sense to consider “equal” as meaning “both instances have the same x values and y values”, and so this is the logic used by the operator implementation.

上記の例では、== 演算子を実装して、2 つの Vector2D インスタンスが同等の値を持つかどうかを確認します。 Vector2D のコンテキストでは、「等しい」を「両方のインスタンスが同じ x 値と y 値を持つ」ことを意味すると考えるのが理にかなっており、これが演算子の実装で使用されるロジックです。

You can now use this operator to check whether two Vector2D instances are equivalent:

この演算子を使用して、2 つの Vector2D インスタンスが同等かどうかを確認できるようになりました。

let twoThree = Vector2D(x: 2.0, y: 3.0)

let anotherTwoThree = Vector2D(x: 2.0, y: 3.0)

if twoThree == anotherTwoThree {

print("These two vectors are equivalent.")

}

// Prints "These two vectors are equivalent."

In many simple cases, you can ask Swift to provide synthesized implementations of the equivalence operators for you, as described in Adopting a Protocol Using a Synthesized Implementation.

多くの単純なケースでは、「合成された実装を使用したプロトコルの採用」で説明されているように、等価演算子の合成された実装を提供するように Swift に依頼できます。

Custom Operators

カスタム演算子

You can declare and implement your own custom operators in addition to the standard operators provided by Swift. For a list of characters that can be used to define custom operators, see Operators.

Swift が提供する標準演算子に加えて、独自のカスタム演算子を宣言して実装することができます。 カスタム演算子の定義に使用できる文字のリストについては、「演算子」を参照してください。

New operators are declared at a global level using the operator keyword, and are marked with the prefix, infix or postfix modifiers:

新しい演算子は、operator キーワードを使用してグローバル レベルで宣言され、prefix、infix、またはpostfix修飾子でマークされます。

prefix operator +++

The example above defines a new prefix operator called +++. This operator doesn’t have an existing meaning in Swift, and so it’s given its own custom meaning below in the specific context of working with Vector2D instances. For the purposes of this example, +++ is treated as a new “prefix doubling” operator. It doubles the x and y values of a Vector2D instance, by adding the vector to itself with the addition assignment operator defined earlier. To implement the +++ operator, you add a type method called +++ to Vector2D as follows:

上の例では、+++ という新しい接頭辞演算子を定義しています。 この演算子には Swift では既存の意味がないため、Vector2D インスタンスを操作するという特定のコンテキストにおいて、以下の独自のカスタムの意味が与えられます。 この例では、+++は新しい「接頭辞倍増」演算子として扱われます。 前に定義した加算代入演算子を使用してベクトルをそれ自体に加算することで、Vector2D インスタンスの x 値と y 値を 2 倍にします。 +++ 演算子を実装するには、次のように +++ という型メソッドを Vector2D に追加します。

extension Vector2D {

static prefix func +++ (vector: inout Vector2D) -> Vector2D {

vector += vector

return vector

}

}

var toBeDoubled = Vector2D(x: 1.0, y: 4.0)

let afterDoubling = +++toBeDoubled

// toBeDoubled now has values of (2.0, 8.0)

// afterDoubling also has values of (2.0, 8.0)

Precedence for Custom Infix Operators

カスタム中置演算子の優先順位

Custom infix operators each belong to a precedence group. A precedence group specifies an operator’s precedence relative to other infix operators, as well as the operator’s associativity. See Precedence and Associativity for an explanation of how these characteristics affect an infix operator’s interaction with other infix operators.

カスタム中置演算子はそれぞれ優先順位グループに属します。 優先順位グループは、演算子の結合性だけでなく、他の中置演算子に対する演算子の優先順位も指定します。 これらの特性が中置演算子と他の中置演算子の相互作用にどのように影響するかについては、「優先順位と結合性」を参照してください。

A custom infix operator that isn’t explicitly placed into a precedence group is given a default precedence group with a precedence immediately higher than the precedence of the ternary conditional operator.

優先順位グループに明示的に配置されていないカスタム中置演算子には、三項条件演算子の優先順位よりすぐ高い優先順位を持つデフォルトの優先順位グループが与えられます。

The following example defines a new custom infix operator called +-, which belongs to the precedence group AdditionPrecedence:

次の例では、優先順位グループ AdditionPrecedence に属する +- という新しいカスタム中置演算子を定義します。

infix operator +-: AdditionPrecedence

extension Vector2D {

static func +- (left: Vector2D, right: Vector2D) -> Vector2D {

return Vector2D(x: left.x + right.x, y: left.y - right.y)

}

}

let firstVector = Vector2D(x: 1.0, y: 2.0)

let secondVector = Vector2D(x: 3.0, y: 4.0)

let plusMinusVector = firstVector +- secondVector

// plusMinusVector is a Vector2D instance with values of (4.0, -2.0)

This operator adds together the x values of two vectors, and subtracts the y value of the second vector from the first. Because it’s in essence an “additive” operator, it has been given the same precedence group as additive infix operators such as + and -. For information about the operators provided by the Swift standard library, including a complete list of the operator precedence groups and associativity settings, see Operator Declarations(Link:developer.apple.com). For more information about precedence groups and to see the syntax for defining your own operators and precedence groups, see Operator Declaration.

この演算子は、2 つのベクトルの x 値を加算し、最初のベクトルから 2 番目のベクトルの y 値を減算します。 これは本質的に「加法」演算子であるため、+ や - などの加法中置演算子と同じ優先順位グループが与えられています。 演算子の優先順位グループと結合性設定の完全なリストを含む、Swift 標準ライブラリによって提供される演算子の詳細については、「演算子の宣言(Link:developer.apple.com)(英語)」を参照してください。 優先順位グループの詳細、および独自の演算子と優先順位グループを定義するための構文を確認するには、「演算子の宣言」を参照してください。

Note

注釈

You don’t specify a precedence when defining a prefix or postfix operator. However, if you apply both a prefix and a postfix operator to the same operand, the postfix operator is applied first.

前置演算子または後置演算子を定義するときに優先順位を指定しません。 ただし、前置演算子と後置演算子の両方を同じオペランドに適用する場合は、後置演算子が最初に適用されます。

Result Builders

結果ビルダー

A result builder is a type you define that adds syntax for creating nested data, like a list or tree, in a natural, declarative way. The code that uses the result builder can include ordinary Swift syntax, like if and for, to handle conditional or repeated pieces of data.

結果ビルダーは、リストやツリーなどのネストされたデータを自然な宣言的な方法で作成するための構文を追加する、ユーザーが定義するタイプです。 結果ビルダーを使用するコードには、条件付きまたは繰り返しのデータを処理するための if や for などの通常の Swift 構文を含めることができます。

The code below defines a few types for drawing on a single line using stars and text.

以下のコードは、星とテキストを使用して単一の線上に描画するためのいくつかのタイプを定義します。

protocol Drawable {

func draw() -> String

}

struct Line: Drawable {

var elements: [Drawable]

func draw() -> String {

return elements.map { $0.draw() }.joined(separator: "")

}

}

struct Text: Drawable {

var content: String

init(_ content: String) { self.content = content }

func draw() -> String { return content }

}

struct Space: Drawable {

func draw() -> String { return " " }

}

struct Stars: Drawable {

var length: Int

func draw() -> String { return String(repeating: "*", count: length) }

}

struct AllCaps: Drawable {

var content: Drawable

func draw() -> String { return content.draw().uppercased() }

}

The Drawable protocol defines the requirement for something that can be drawn, like a line or shape: The type must implement a draw() method. The Line structure represents a single-line drawing, and it serves the top-level container for most drawings. To draw a Line, the structure calls draw() on each of the line’s components, and then concatenates the resulting strings into a single string. The Text structure wraps a string to make it part of a drawing. The AllCaps structure wraps and modifies another drawing, converting any text in the drawing to uppercase.

Drawable プロトコルは、線や図形など、描画できるものの要件を定義します。型は、draw() メソッドを実装する必要があります。 Line 構造は単一線の描画を表し、ほとんどの描画の最上位コンテナとして機能します。 Line を描くために、この構造は線の各コンポーネントでdraw()を呼び出し、結果の文字列を単一の文字列に連結します。 Text 構造は文字列をラップして描画の一部にします。 AllCaps 構造は、別の描画をラップして変更し、描画内のテキストを大文字に変換します。

It’s possible to make a drawing with these types by calling their initializers:

これらの型の初期化子を呼び出すことで、これらの型を使用して描画を作成できます。

let name: String? = "Ravi Patel"

let manualDrawing = Line(elements: [

Stars(length: 3),

Text("Hello"),

Space(),

AllCaps(content: Text((name ?? "World") + "!")),

Stars(length: 2),

])

print(manualDrawing.draw())

// Prints "***Hello RAVI PATEL!**"

This code works, but it’s a little awkward. The deeply nested parentheses after AllCaps are hard to read. The fallback logic to use “World” when name is nil has to be done inline using the ?? operator, which would be difficult with anything more complex. If you needed to include switches or for loops to build up part of the drawing, there’s no way to do that. A result builder lets you rewrite code like this so that it looks like normal Swift code.

このコードは機能しますが、少し扱いにくいです。 AllCaps の後に深く入れ子になった括弧は読みにくいです。 名前がnilの場合に「World」を使用するフォールバックロジックは、??を使用してインラインで実行する必要があります。 これは、より複雑なものでは困難になるでしょう。 描画の一部を構築するためにスイッチや for ループを含める必要がある場合、それを行う方法はありません。 結果ビルダーを使用すると、このようなコードを通常の Swift コードのように書き直すことができます。

To define a result builder, you write the @resultBuilder attribute on a type declaration. For example, this code defines a result builder called DrawingBuilder, which lets you use a declarative syntax to describe a drawing:

結果ビルダーを定義するには、型宣言に @resultBuilder 属性を記述します。 たとえば、次のコードは、DrawingBuilder という結果ビルダーを定義します。これにより、宣言構文を使用して図面を記述することができます。

@resultBuilder

struct DrawingBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Drawable...) -> Drawable {

return Line(elements: components)

}

static func buildEither(first: Drawable) -> Drawable {

return first

}

static func buildEither(second: Drawable) -> Drawable {

return second

}

}

The DrawingBuilder structure defines three methods that implement parts of the result builder syntax. The buildBlock(_:) method adds support for writing a series of lines in a block of code. It combines the components in that block into a Line. The buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) methods add support for if–else.

DrawingBuilder 構造では、結果ビルダー構文の一部を実装する 3 つのメソッドが定義されています。 buildBlock(_:) メソッドは、コード ブロックに一連の行を記述するためのサポートを追加します。 そのブロック内のコンポーネントを 1 つの線に結合します。 buildEither(first:) メソッドと buildEither(second:) メソッドは、if-else のサポートを追加します。

You can apply the @DrawingBuilder attribute to a function’s parameter, which turns a closure passed to the function into the value that the result builder creates from that closure. For example:

@DrawingBuilder 属性を関数のパラメータに適用すると、関数に渡されたクロージャが、結果ビルダーがそのクロージャから作成する値に変換されます。 例えば:

func draw(@DrawingBuilder content: () -> Drawable) -> Drawable {

return content()

}

func caps(@DrawingBuilder content: () -> Drawable) -> Drawable {

return AllCaps(content: content())

}

func makeGreeting(for name: String? = nil) -> Drawable {

let greeting = draw {

Stars(length: 3)

Text("Hello")

Space()

caps {

if let name = name {

Text(name + "!")

} else {

Text("World!")

}

}

Stars(length: 2)

}

return greeting

}

let genericGreeting = makeGreeting()

print(genericGreeting.draw())

// Prints "***Hello WORLD!**"

let personalGreeting = makeGreeting(for: "Ravi Patel")

print(personalGreeting.draw())

// Prints "***Hello RAVI PATEL!**"

The makeGreeting(for:) function takes a name parameter and uses it to draw a personalized greeting. The draw(_:) and caps(_:) functions both take a single closure as their argument, which is marked with the @DrawingBuilder attribute. When you call those functions, you use the special syntax that DrawingBuilder defines. Swift transforms that declarative description of a drawing into a series of calls to the methods on DrawingBuilder to build up the value that’s passed as the function argument. For example, Swift transforms the call to caps(_:) in that example into code like the following:

makeGreeting(for:) 関数は name パラメータを受け取り、それを使用してパーソナライズされた挨拶を描画します。 draw(_:)関数と caps(_:)関数は両方とも、@DrawingBuilder 属性でマークされた単一のクロージャを引数として受け取ります。 これらの関数を呼び出すときは、DrawingBuilder が定義する特別な構文を使用します。 Swift は、描画の宣言的な記述を DrawingBuilder のメソッドへの一連の呼び出しに変換し、関数の引数として渡される値を構築します。 たとえば、Swift は、この例の caps(_:) への呼び出しを次のようなコードに変換します。

let capsDrawing = caps {

let partialDrawing: Drawable

if let name = name {

let text = Text(name + "!")

partialDrawing = DrawingBuilder.buildEither(first: text)

} else {

let text = Text("World!")

partialDrawing = DrawingBuilder.buildEither(second: text)

}

return partialDrawing

}

Swift transforms the if–else block into calls to the buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) methods. Although you don’t call these methods in your own code, showing the result of the transformation makes it easier to see how Swift transforms your code when you use the DrawingBuilder syntax.

Swift は、if-else ブロックを buildEither(first:) メソッドと buildEither(second:) メソッドの呼び出しに変換します。 これらのメソッドを独自のコードで呼び出すわけではありませんが、変換の結果を表示すると、DrawingBuilder 構文を使用するときに Swift がコードをどのように変換するかを簡単に確認できます。

To add support for writing for loops in the special drawing syntax, add a buildArray(_:) method.

特別な描画構文での for ループの記述のサポートを追加するには、buildArray(_:) メソッドを追加します。

extension DrawingBuilder {

static func buildArray(_ components: [Drawable]) -> Drawable {

return Line(elements: components)

}

}

let manyStars = draw {

Text("Stars:")

for length in 1...3 {

Space()

Stars(length: length)

}

}

print(manyStars.draw())

//Prints "Stars: * ** ***"In the code above, the for loop creates an array of drawings, and the buildArray(_:) method turns that array into a Line.

上記のコードでは、for ループによって描画の配列が作成され、buildArray(_:) メソッドによってその配列が Line に変換されます。

For a complete list of how Swift transforms builder syntax into calls to the builder type’s methods, see resultBuilder(Link:developer.apple.com).

Swift がビルダー構文をビルダー タイプのメソッドの呼び出しに変換する方法の完全なリストについては、resultBuilder(Link:developer.apple.com)(英語)を参照してください。